"If I belong to a tradition it is a tradition that makes the masterpiece tell the performer what he should do and not the performer telling the piece what it should be like, or the composer what he ought to have composed."

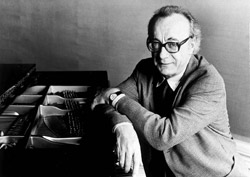

Alfred Brendel's place among the greatest musicians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is assured. Renowned for his masterly interpretations of the works of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and Liszt, he is one of the indisputable authorities in musical life today and one of the very few living pianists whose name alone guaranteed a sell-out anywhere in the world he chooses to play.

Yet Brendel had a most untypical start compared to most of his peers. He was not a child prodigy, his parents were not musicians, there was no music in the house and, as he admits himself, he is neither a good sight-reader nor blessed with a phenomenal memory.

His ancestors are a mixture of German, Austrian, Italian and Slav. He was born on 5 January 1931 at Wiesenberg, northern Moravia (now the Czech Republic) and spent his childhood travelling throughout Yugoslavia and Austria.

At various times his father worked as an architectural engineer, businessman and resort hotel manager on the Adriatic island of Krk. Here, young Alfred first encountered "more elevated" music. "I operated the record player which I wound up and put on the records for the guests of the hotel which were operetta records of around 1930 sung by Jan Kiepura. And I sang along and found it to be rather easy."*

His father then went to Zagreb and became the director of a cinema. Here Alfred Brendel was given his first piano lessons at the age of six from Sofia Dezelic (he also appeared at a children's theatre in Zagreb) and had a succession of early teachers as the family moved on, returning after the War to a place near Graz where Brendel pere worked in a department store.

Here Alfred studied at the Graz Conservatory with Ludovika von Kaan (who had studied with one of Liszt's more illustrious pupils, Bernhard Stavenhagen) as well as private composition lessons with Artur Michl, a local organist and composer. After the age of sixteen, the little formal training he had had came to an end. Apart from attending a few master classes he had no further teachers. To this day, Alfred Brendel regards his unconventional musical background as something of an advantage.

"A teacher can be too influential," he feels. "Being self-taught, I learned to distrust anything I hadn't figured out myself." More valuable than teachers was listening to other pianists, conductors and singers - and himself. Presented with a Revox tape-recorder (now an antediluvian machine but still in working order), Brendel learnt by recording the piece he was studying, listening to himself and reacting to it. "I still think that for young people today this is a very good way to get on," he says, "and it makes some of the functions of a teacher obsolete."*

Brendel gave his first public recital in Graz age 17, boldly entitled 'The Fugue in Piano Literature' with works by Bach, Brahms and Liszt. "It consisted," he recalls, "only of piano works with fugues and of four encores which also contained fugues. “

One of these pieces was a sonata of my own with a double fugue, of course. At that time I composed polyphonic pieces with great pleasure, and a habit to listen to all voices implied in a composition has stayed with me."*

As well as his musical activities, Brendel also pursued his other interests, including painting, composing and literature, of which literature became his second professional occupation. At the time of his first recital there was a one-man exhibition of his water-colours in a Graz gallery. But in 1949 he won fourth prize in the prestigious Busoni Competition in Bolzano, Italy. It was enough to launch his career as a performing musician.

He then toured throughout Europe and Latin America, slowly, unspectacularly building his career, and participating in a few masterclasses of Paul Baumgartner, Eduard Steuermann (a pupil of Busoni and Schoenberg, and who gave many first performances of the latter's work) and, most importantly, the great Swiss pianist Edwin Fischer. He, Alfred Cortot and Wilhelm Kempff can be said to have had most influence on Brendel's playing. However, Brendel maintains that he has profited most from listening to singers and conductors. Later, one of his Lied partners was Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.

Brendel remembers, "When I was young my overall career wasn't sensational at all, it rather progressed step by step. But then, one day I was performing a Beethoven programme in the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London.

It was quite an unpopular programme, I didn't even like it much myself and the next day I got three offers from big record companies. It seemed really rather grotesque, like a slow, hardly noticeable rise on a thermometer or a kettle warming water suddenly beginning to boil and to bubble and the steam comes out."*

During the 1950s he made his first recordings. These served to confirm his stature as an authoritative keyboard artist and, during the 1960s, became the first pianist ever to record the entire piano works of Beethoven (on the Vox label), a set which, in the opinion of one critic, contains 'some of the finest Beethoven ever recorded'. In the 1970s, Brendel returned to Beethoven with a complete cycle of the piano sonatas on the Philips label for which he now recorded exclusively.

During the 1982-83 season he presented cycles of all 32 Sonatas in the course of 77 recitals in 11 cities throughout Europe and America. No pianist since the legendary Artur Schnabel forty years before had played the complete Beethoven Sonatas at Carnegie Hall. It was a venture he repeated throughout the world during the 1990s and a third recorded cycle of all the Beethoven Sonatas was completed in 1996.

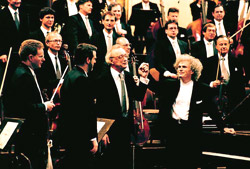

Three years later saw the appearance of new recordings of all five Beethoven Piano Concertos in an acclaimed partnership with Sir Simon Rattle and the Wiener Philharmoniker. In 1999, Carnegie Hall invited him to be musician in residence with an unprecedented series of seven events in a variety of roles - solo recitalist, Lieder collaborator, chamber musician, orchestral soloist and performer of his own poems. To mark his 70th birthday in 2001, Alfred Brendel performed in a series of residences at prestigious concert halls in cities throughout the world, including Vienna, London, Paris and Tokyo.

Brendel's discography is now among the most extensive of any pianist, reflecting a repertoire of solo and orchestral works that ranges from Bach and Haydn to Weber to Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, Mussorgsky and Schoenberg.

He is one of the few pianists to have recorded all of the Mozart piano concertos (with Sir Neville Marriner and the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields). As well as playing a prominent role in championing Schubert's Piano Sonatas, he has recorded two complete cycles of his mature piano works, 1822-28, as well as establishing Schoenberg's Piano Concerto in the concert repertoire. During the 1990s, Brendel releases included Brahms' Second Piano Concerto (with Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic), sonatas by Haydn, Mozart solo recitals, as well as a new recording of Liszt's B minor Sonata, Funerailles and four late pieces. To celebrate his 65th birthday in 1996, Philips released a 25-disc boxed set entitled The Art of Alfred Brendel.

In the first years of this century, he recorded 8 of Mozart’s concertos with Sir Charles Mackerras, cooperated with Matthias Goerne in two Schubert discs, and played all of Beethoven’s works for piano and cello with his son Adrian. Recently, in a double CD series, he has selected some of this own favourites on record including a number of live performances from the BBC; this series is called ‘Artist’s Choice’.

What sort of man is he, this apparently austere, intellectual musician who has dedicated his life to the cornerstones of the piano repertoire? Sir Simon Rattle recalls that "I was right at the beginning of my twenties when I first worked with him and he's since become a very good friend. But I can remember the first performance just thinking what he is asking me to do is so difficult and is such a stretch. I really despaired at one point that I would ever be able to. Nowadays what he asks is just bloody difficult instead of completely impossible and we've done so much together that I think we understand each other's rhythms."*

Since 1971, he and his wife Irene have made their home in London. "His inspiration comes from art and then from painting and from literature, from being inside himself rather than extending himself out except when he plays as a performer. I think he lives with his very strong sense of the time he still has to achieve what he wants to achieve and he is very economical with his forces and his energies. He wants to use them for what he seriously wants to do."*

Marie-Francoise Bucquet, a friend of the Brendels, goes further. "I think he is very strong and at the same time he's very afraid of his emotions like all people who have very strong emotions. When he was younger I think there was a turmoil in him - there was more than that. There was a fire which he was afraid to show and which came out in his playing. Now I find that he is more and more reconciled. I think he has integrated the person he wanted to be. The Mozart playing nowadays is for me the proof that he has become very natural. He can express himself, there is no barrier now between the person he is and the person who goes on stage."*

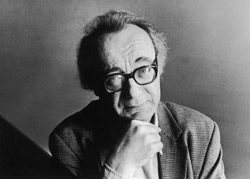

Unusually tall for a pianist (he has suffered from back problems in the past), with his trademark heavy spectacles and high forehead accentuated by a central raft of wayward swept back hair, Brendel's is one of the most instantly recognisable faces of any musician. With his famous facial grimaces in performance and frequently bandaged fingers, Brendel's art is a byword for perfection, profundity, self-effacement and textual illumination. There is, on the surface, nothing that is flip or casual about him. Yet look at almost every photograph and his eyes are either twinkling mischievously or raised in quizzical amusement.

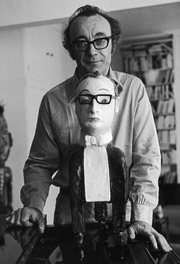

Brendel's extra-musical interests manifest another side to the single-minded purveyor of the central European piano repertoire, ranging from Romanesque churches and Baroque architecture to Dada and Edward Gorey, from Shakespeare to nonsense verse and the cartoons of Charles Addams and Gary Larson.

He is fascinated with the grotesque and the fantastic, and collects kitsch, primitive masks and newspaper bloopers. "He and his wife really have a large circle of friends," observes one of them, Professor Bernard Williams, "people who do lots of different things and one sees a lot of interesting people, and he gives everybody a lot not just by his playing but by his conversation and by the kind of friendship he offers. But I think he gets quite a lot out of it too. There's a saying that he's rather fond of, that 'Humour is the sublime in reverse'. I think that does catch an aspect of his thought. He thinks that, as it were, certain kinds of jokes, certain kinds of paradox are actually the deepest way of representing important things."* Listing "laughing" as his favourite occupation, his 1984 Darwin Lecture at Cambridge University dealt with the subject "Does classical music have to be entirely serious?" and his playing shows a rare talent for highlighting unexpected elements of humour, particularly in Haydn and Beethoven.

Writing is a constant source of inspiration and expression for Alfred Brendel. He has published two collections of articles and lectures: Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts Robson Books, (1976) and Music Sounded Out Robson Books, (1990) full of the same intellectual rigour and sly wit that he brings to his keyboard playing. Recently, all his essays have been gathered in “Alfred Brendel on Music” (new edition, JR Books 2007). A book of conversations with Martin Meyer, “The Veil of Order” (in the US: “Me of all people”) was published by Faber in 2002.

“One Finger Too Many”, has seen him depart from his usual role as a music essayist in a volume of absurd poetry. A second poetry selection in English is called “Cursing Bagels”. The literary press has praised his work on its own merit, setting aside his musical renown. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung lauded his writings as "a collection of texts which can be numbered among the sparse ranks of genuinely comic literature and which make their author possibly 'immortal"'.

'Playing the Human Game' a collected edition of his poems, has been published by Phaidron Press in 2010.

"I am not exclusively a musician, as the past few years have clearly shown," says Brendel. "I now lead a kind of double life. There has been an upsurge of my literary life with frequent poetry readings and Collected Poems in German and French. I am looking forward to my retirement from the stage to do more writing and lecturing”.

Brendel has been recipient of many major music prizes, including the Leonie Sonning Prize 2002, Ernst von Siemens-Musikpreis 2004, Prix Venezia: Premio Artur Rubinstein 2007, Praemium Imperiale Tokyo 2008 and Herbert von Karajan Prize 2008. He received the Hans von Bülow Medal of the Berlin Philharmonic 1992, the Beethoven-Ring of the Vienna Music University 2001, the Franz Liszt Ehrenpreis 2011, the Juillard Medal 2011 and the Golden Mozart Medal of the Salzburg Mozarteum 2014.

In 1998 he was made an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic, sharing this distinction with only two other pianists, Emil von Sauer and Wilhelm Backhaus.

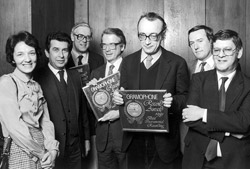

He received Lifetime Achievement Awards by Edison, Midem Classical Awards, Deutscher Schallplattenpreis and The Gramophone. There has also been a string of Honorary Doctorates including those from the Universities of London 1978, Oxford 1983, Yale 1992, McGill Montreal 2011 and Camebridge 2012.

Among Music Schools, Honorary Degrees came from the Royal College of Music, London 1999, Boston New England Conservatory 2009, Hochschule Franz Liszt Weimar 2009 and The Juillard School 2011.

On 26 April 1998, Alfred Brendel celebrated 50 years of public performances. As he approached this next significant milestone in his eventful life, what of the future? "There have been in my career periods where I concentrated mainly on one particular composer. Not long ago there has been an extended Beethoven period, now in these years I feel that I should turn my attention to Mozart and particularly to his Sonatas, even if they are 'too difficult for artists while too easy for children' as Schnabel has so admirably said. I told myself that if I don't try to make sense of them now it may be too late."*

After his final concert with the Vienna Philharmonic in December 2008, which has been preserved as a Decca recording, he has remained active lecturing, writing, giving readings of his poetry, and teaching master classes. In America, the venues of his lectures have included Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Berkeley, McGill and New York University, in Europe Oxford and Camebridge as well as various music festivals.

* from Alfred Brendel - Man and Mask, a Rosetta Pictures production for the BBC and ZDF in association with ARTE.

Jeremy Nicholas

revised April 2008